Fast, Stable, Secure. Meet Drive 2.0

The FieldView Drive 2.0 can send seed scripts without a thumb drive, has built-in GPS, offers faster data syncing and compatibility with a wider range of equipment.

The smart farm: it’s a concept we’re all familiar with today. That’s thanks to the work of a few innovators in agricultural technology. Let’s meet some of them.

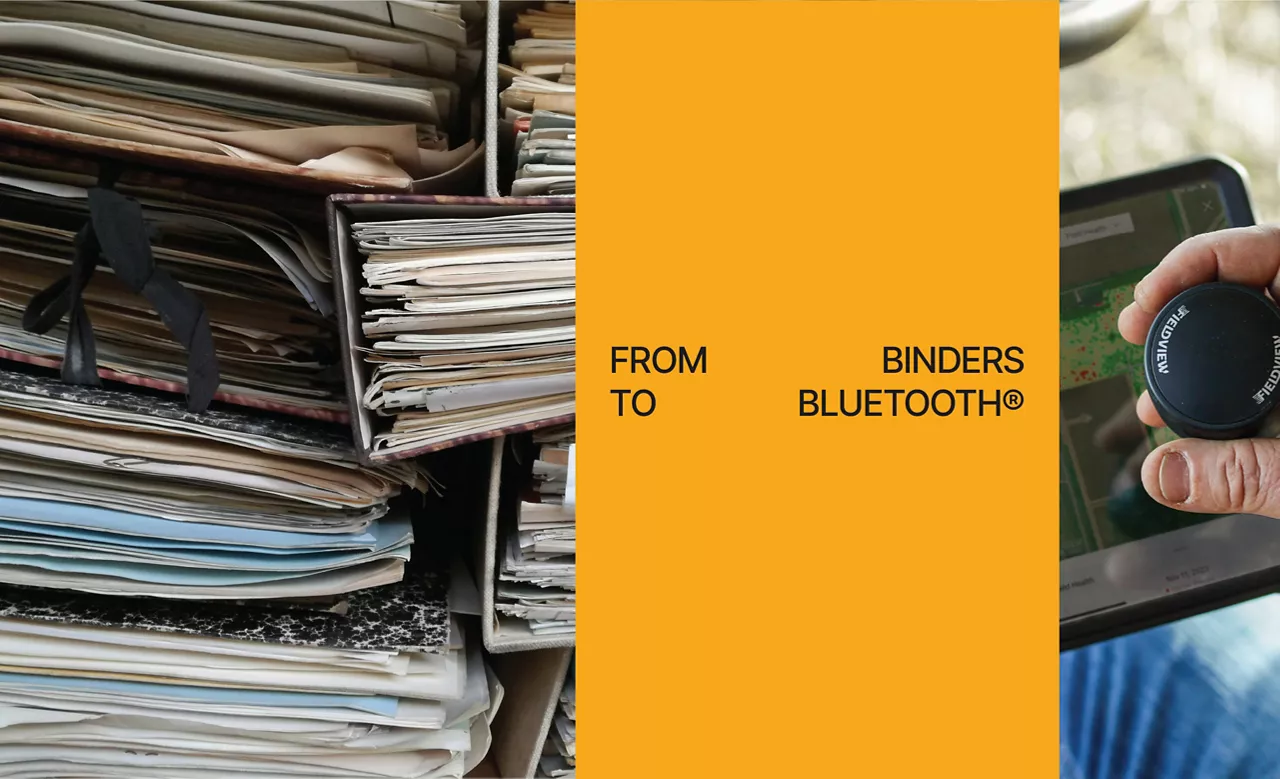

Farmers are no strangers to data. Anyone who’s grown up on a farm will vividly remember stacked shelves of binders filled with field and yield data, Farmers’ Almanacs and historical records. A wealth of information, but entirely analogue and tricky to model around. How could you make that data easier to collect and act on? How could you go from binders to iPads? That’s what FieldView and the original Drive were designed to solve.

However it may appear in hindsight, there was nothing obvious or predestined about the creation of digital farming. It’s a story of disparate leaders, working on separate breakthroughs, coming together to help farmers do what they do better. Let’s meet some of the early founders and startups that made it all possible.

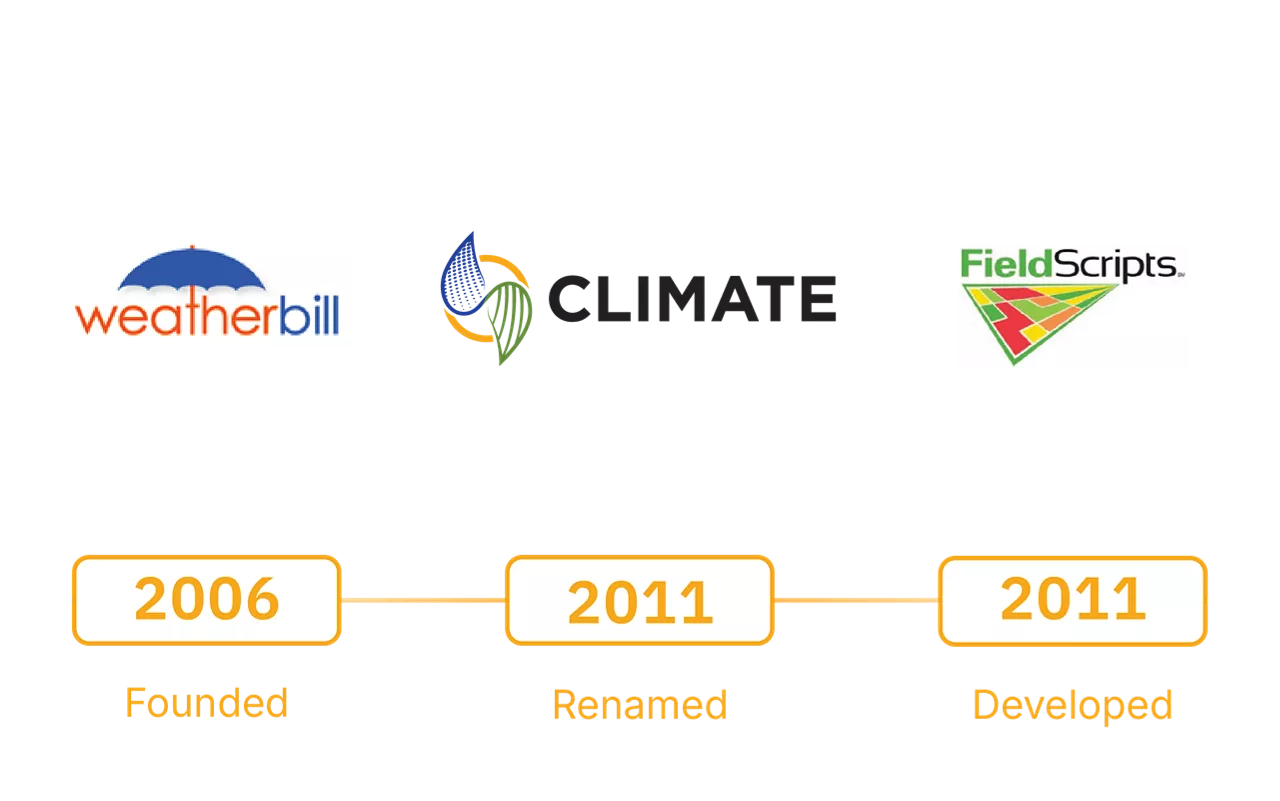

Our story starts with two engineers from Silicon Valley: David Friedberg and Siraj Khaliq. The two founded WeatherBill, a business inspired by their favorite San Francisco bike shop. On rainy days, no one rented bikes—so the bike shop made no money. Friedberg and Khaliq realized they could use National Weather Service data to create actuarial models that provided weather insurance to hedge against unexpected weather, such as particularly wet summers.

At the beginning, the company served any client concerned about the weather: outdoor TV and film production, farmers and food producers and, of course, the San Francisco bike shop that started everything. But, as time went on, farmers and agricultural businesses became their largest segment. After all, few industries are more subject to the weather than agriculture.

Jeff Hamlin, the company’s sixth hire, remembers his first week at the company in February of 2007. “I opened the business section of the San Francisco Chronicle, and the front page story was about the deep freeze that winter,” he recalls. Inclement weather destroyed up to three-quarters of California's annual $1 billion citrus crop. “They quoted Philip LoBue, a farmer, citrus packer and chairman of California Citrus Mutual. He said, ‘I had to lay off 80% of my workforce because of this weather. If this happens next year, we’ll be out of business.’ And so I called him up and said, ‘I can sell you weather insurance.’ He bought a policy.”

As WeatherBill grew, agriculture clients and agriculture-adjacent clients became overwhelmingly the largest share of the business. So, like all good founders, they pivoted their offering to serve that demand.

By 2011, and after a name change to The Climate Corporation in 2011, the company received USDA authorization to provide crop insurance and began focusing primarily on agriculture clients.

Meanwhile, two Indiana-based engineers created the earliest prototypes of FieldScripts in 2011. These scripts enabled growers to execute variable seed-planting rates, based on the properties of different hybrid seeds.

But this was primarily a tool for managing inputs, and the team saw a greater opportunity: to provide solutions that could advise farmers and increase the productivity of their yields. Tom Verseman, Digital Enablement Marketing Lead at Bayer, discusses the observation that brought the size of the opportunity into focus:

“At the 2015 NCGA (National Corn Growers’ Association) awards, the winner for highest yield managed 532 BU/AC (bushels/acre). The national average that year was 168. That 364 BU/AC gap represented the size of the opportunity. But what we really cared about was this: how can we use data to help farmers achieve that next 5, 10, bushels per acre? That’s what FieldView was created to achieve.”

To achieve those bushels, the next step was bringing together the data that could provide the comprehensive yet personalized insights and analysis farmers needed.

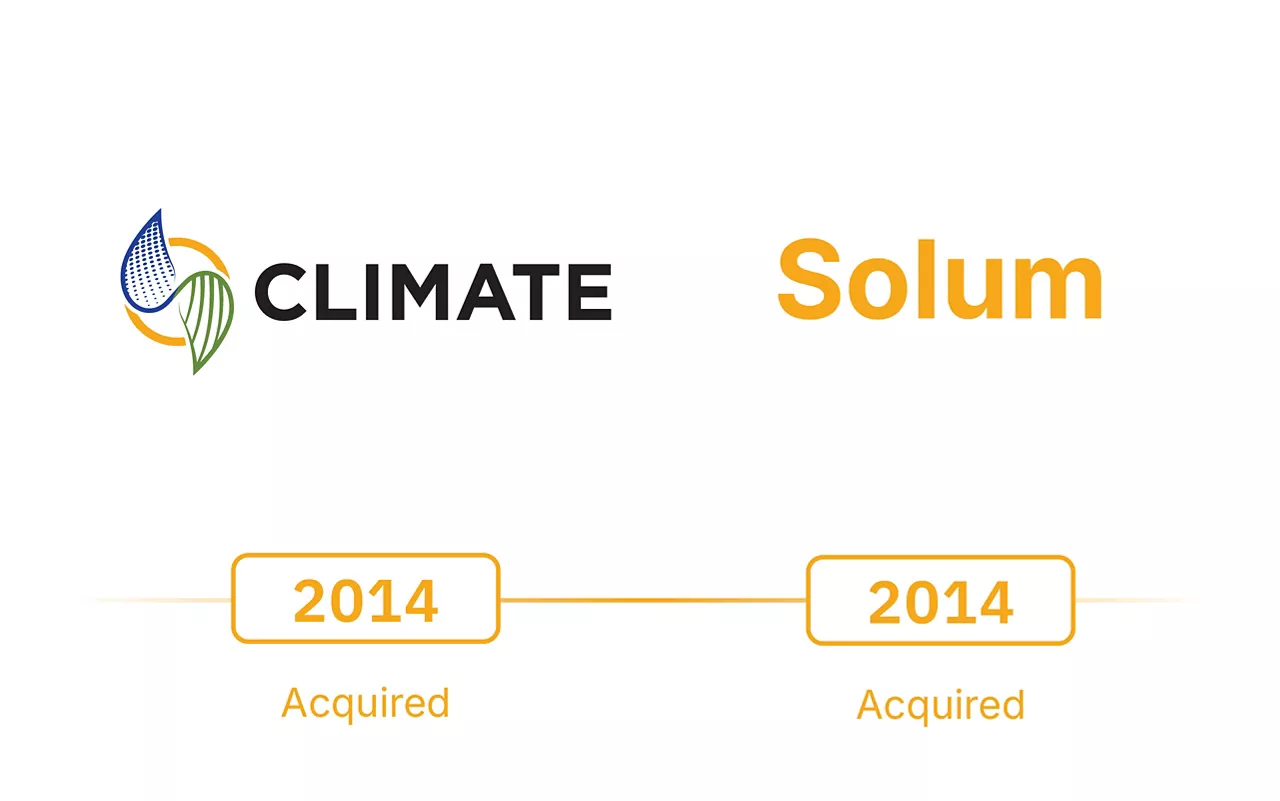

The Climate Corporation was acquired in 2014 for $1bn, setting the stage and providing the capital investment for the radical new project of digital farming.

Wes Hays, former commercial product director at the company, sees this as a pivotal moment in the development of FieldView. “The purchase of the Climate Corporation showed the world that [we were] very serious about digital farming. You don't spend a billion dollars just for nothing.”

Also in 2014, a soil-testing company called Solum, operating out of Ames, Iowa, was bought. The founders of Solum were particularly interested in optimizing the input of nitrates into farmland to protect the environment. As founder Nick Koshnick observed, “This is the place where sustainability is directly in line with economic support." A suite of hardware and software tools now enabled The Climate Corporation to analyze the chemical makeup of farmers’ fields.

A new, larger Climate Corporation now had access to almost everything it needed: detailed soil analysis, weather and climate data, plus the ability to create scripts that took advantage of that information to improve crop density and yields.

For Wes Hays, the revolution was more than professional: it was personal. “I accepted the job to work on FieldScripts, sold my house in four days and a week later it was announced we were buying The Climate Corporation. We moved to St. Louis from Western Iowa. I started in December of 2013 and by May 2014, we’d folded everything into The Climate Corporation. I was one of maybe twelve people to help get it off the ground and integrate it into the rest of our business.”

Digital farming had reached an inflection point. The data was there. The tools were there. But they weren’t yet unified in a single system that could pull information from tractors and other equipment and help farmers apply it in the field.

In December 2014, the company acquired 640 Labs, an ag-tech startup based in Chicago. Founders Craig Rupp and Corbett Kull had developed the 640Drive, 3D printed to save money, which used the diagnostic port on farming equipment to capture data. 640 Labs (so named because there are 640 acres in a square mile) wanted to put farmers’ own data back in their hands.

Pat Dumstorff, then vice president of sales and marketing, noted at the time, “Agriculture is incredibly underserved right now when it comes to data and cloud solutions, and it’s a fascinating industry for us to get into.”

After acquiring 640 Labs, and with input from the broader team, The Climate Corporation built what went on to become the very first FieldView Drive device. Using their initial concept—connecting to the diagnostic port—but adding Bluetooth® connectivity, the FieldView Drive became the portal to downloading and sharing script data, and recording and sending information back to FieldView.

For Tom Verseman, this was the moment the company had been waiting for: “The FieldView Drive was a game changer for the connected cab.”

Now, with FieldView providing analysis and advice, farmers could create data-driven, customized scripts, then sync and share them with any of their own vehicles, plus third-party contractors. Farming was now connected, data-driven and shareable: in other words, it was digital.

In the decade since the launch of the FieldView Drive, farmers have flocked to adopt the new technology. Hundreds of millions of acres now use the system, across dozens of countries. Productivity gains have followed. From a national average corn yield of 168 BU/AC in 2015, the USDA has forecast a record 188—double the already ambitious five-to-ten increase the team first set out to achieve.

Yet, for many farmers, FieldView is about more than productivity—it’s about legacy. As Tom puts it, “You can now pass your entire farm down, every bit of information, in one neat package. It’s something I’ve thought about more and more as I’ve had my own family, my own kids.”

Now, with the launch of the FieldView Drive 2.0, farmers will have access to even more capabilities in a faster, cutting-edge device. The future is bright for digital farming.