Seven Helpful Reminders for Planting Season

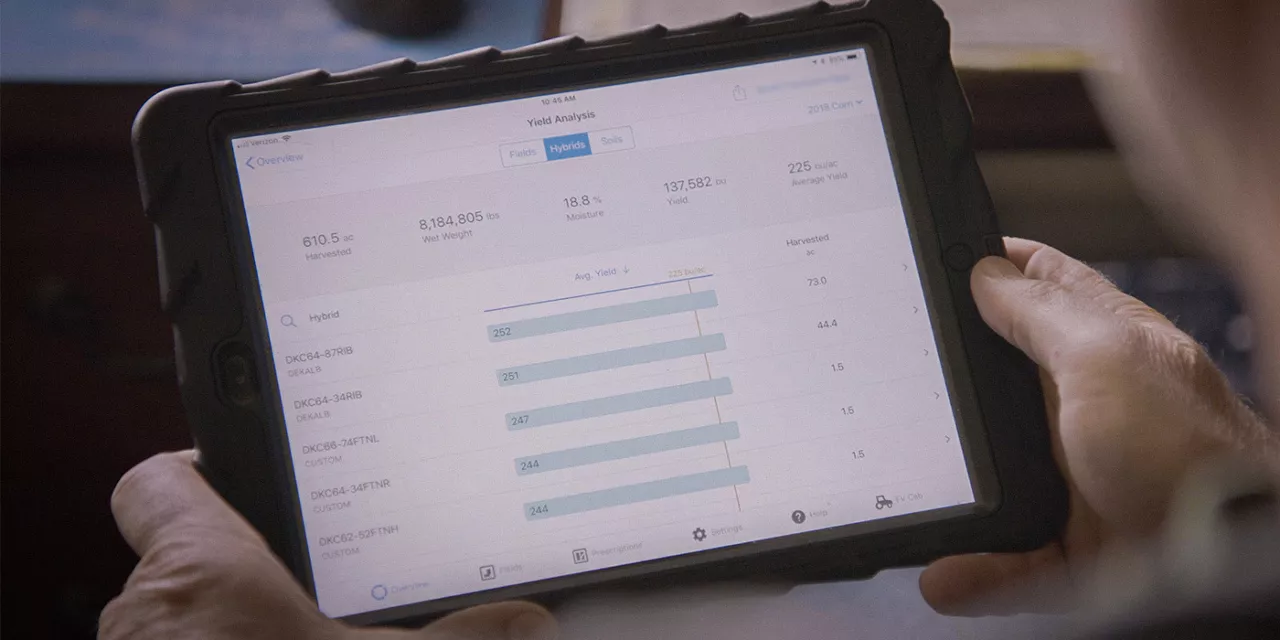

Prepare for planting season with these seven essential reminders. Ensure your equipment is compatible, map field boundaries, preload seed data, update the FieldView Cab app, sync your data and install the FieldView™ Drive 2.0 for seamless precision farming. Learn how FieldView™ helps you track and optimize every step.

?fmt=webp)